We frequently read Australian diet and health articles that recommend we follow the Australian Dietary Guidelines and avoid ‘fad’ diets that cut out whole foods groups. Sometimes it seems that the Dietary Guidelines are used as weapon against those who dare to challenge the meat and dairy centred dietary paradigm. One could argue that having a special food group for baby cow growth fluid makes no biological sense but for the purpose of today’s discussion we are not challenging the scientific validity of the Australian Dietary Guidelines 2013. They were, after all, developed by nutrition experts who reviewed 55 000 research publications.

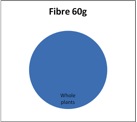

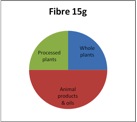

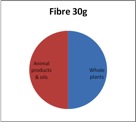

It can appear awkward to fit a whole food plant-based diet to the Australian dietary guidelines. The chart in the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (2013) purports to be representing ‘food groups’ but is actually skewing the focus onto nutrients, in particular by grouping two ‘food groups’ that are heavily marketed as being high in protein and calcium respectively. This can become a problem when someone eating a WFPB diet comes in contact with a dietitian or nutritionist who is rigidly following the guidelines and suggests daily meal plans based on the Recommended number of serves for adults. The results we see are newcomers to WFPB struggling to digest the recommended 2 cups of legumes each day or females over 50 finding it hard to drink 4 cups of plant milk per day. Protein and calcium are found in so many whole plant foods but this is not acknowledged when following the guidelines rigidly. Broadly speaking though, a WFPB diet does fit with the dietary guidelines. We’ll tick these off one by one.

Guideline 1: Maintain a healthy weight, be physically active and eat an amount of nutritious food and drink to meet your energy needs.

Compliance: WFPB is ideal for maintaining a healthy weight, the ingredients are all nutritious and energy needs can be met by eating adequate quantities of grains, starchy vegetables and legumes. ✔

Guideline 2: Enjoy a variety of foods from the five foods groups

Compliance:

Group 1 – Vegetables and legumes ✔

Group 2 – Fruit ✔

Group 3 – Grain foods (mostly whole grain or high fibre) – we do better than “mostly”. ✔

Group 4 – Lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds, and legumes/beans.

This is considered the ‘meat group’ or ‘protein group’ with high protein plant foods included as alternatives for vegetarian/vegan diets. On a WFPB diet much of our protein comes from moderate protein content foods such as whole grains and potatoes but these don’t count towards the ‘meat group’ – the meat and dairy based food group paradigm is not ideal for building a plant-based diet. However we can do it with a legume-rich diet and/or more nuts, seeds and tofu (but we don’t actually need these to meet our protein needs). ✔

Group 5 – Milk, yoghurt, cheese and/or alternatives, mostly reduced fat. That “mostly” word again – in this instance, facilitating the consumption of high saturated fat dairy foods such as cheese. We could tick the dairy group by consuming a lot of plant milks and plant yoghurts but these are not ‘whole’ plant foods. The guidelines do not specify the nature of the ‘alternatives’ so we can replace dairy with any foods that provide a similar range of nutrients. Many whole plant foods are rich in calcium – a cup of chopped kale, for example, provides as much absorbable calcium as a cup of milk. ✔

And drink plenty of water. We can do this. Furthermore, whole plant foods are generally bulky and have a high water content. ✔

Guideline 3: Limit intake of foods containing saturated fat, added salt, added sugars and alcohol.

a) Lists high saturated fat foods. Recommends replacing these foods with food and food products which are high in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Low fat diets are unsuitable for children under 2 years.

Compliance: WFPB foods are all very low in saturated fat (except coconut which we don’t recommend) so we don’t need to replace anything with unsaturated fat.

The idea that children under that age of 2yr can only thrive on the high fat diet of the modern developed nations is puzzling but we are not questioning the guidelines in this exercise. Breast milk (and substitutes) are high in fat by design. There are many higher fat WFPB foods such as nut, seeds, avocados and soy products that can be utilised to design a non-low fat diet for this age group. ✔

b) Limit intake of foods and drinks containing added salts.

Compliance: WFPB is based on unprocessed foods that are very low in salt. We consume some salt from bread and condiments but we recommend these are kept to a minimum. ✔

c) Limit intake of foods with added sugars.

Compliance: WFPB sometimes includes added sugars (e.g. in condiments) but we recommend these are kept to a minimum. ✔

d) Limit alcohol intake.

Compliance: Alcohol is not a WFPB food. ✔

Guideline 4: Support breast feeding.

Compliance: WFPB supports maternal health and reduces environmental contaminants which can end up in breast milk. Mum is eating the plants on behalf of the infant. ✔

Guideline 5: Store and prepare food safely.

Compliance: Most food poisoning bacteria enter our food supply through animal products. We wash our produce and refrigerate left overs. ✔

Dietary Guidelines Review 2023

The Australian Dietary Guidelines (2013) are up for review and ourselves, along with the health charity Doctors For Nutrition are participating in the review at the appropriate times when public consultation is invited:

- Australian Dietary Guidelines review scoping survey – Doctors For Nutrition (2021)

- The role of national dietary guidelines in attaining a healthy and sustainable food system – Doctors For Nutrition (2021)

- Note that the Australian Dietary Guidelines review has been delayed, with the anticipated timeline of 2023 being pushed out to 2025 for its draft and completion – See Anticipated timelines for the revision of the Australian Dietary Guidelines

Resources

- Australian Dietary Guidelines – (2013) Eat For Health

- Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (2013) – shows the visual representation of the 5 food groups

- Recommended number of serves for adults – this table is also on p.41 of the ADG Summary document under a table with the heading ‘Sample daily food patterns for adults’

- The Physicians Committee’s Influence on the Dietary Guidelines and MyPlate – shows PCRM’s Power Plate based on 4 plant-based food groups

- Major Problems With the New Dietary Guidelines (2021) – Exam Room Podcast, PCRM

- Egg Industry Continues To Influence Dietary Guidelines, FOIA Document Reveals – PCRM, 2019

- X Expert is as expert does: in defence of US dietary guidelines (September 2015)

- Dr. Campbell’s recommendations for Dietary Guidelines – T. Colin Campbell, PhD, 2015

Page created 6 January 2023

Last updated 16 June 2023